The activist movement that I chose to explore was the Deaf President Now movement. Growing up as a deaf person in close proximity to Gallaudet, I heard (or rather, saw) this story told over and over. Although it was never explicitly labeled an activist movement, it was an attempt to make a change for the better by those who were not in power, an idea which rings true throughout our history.

The activist movement that I chose to explore was the Deaf President Now movement. Growing up as a deaf person in close proximity to Gallaudet, I heard (or rather, saw) this story told over and over. Although it was never explicitly labeled an activist movement, it was an attempt to make a change for the better by those who were not in power, an idea which rings true throughout our history.

The themes of triumph and pride in the Deaf community were constantly reiterated in these tellings, drawing a very black-and-white picture of the Deaf President Now movements and its success.

The beginning of the story can be traced back to the chartering and founding of Gallaudet University in 1864, presided over by Edward Miner Gallaudet, a hearing man. Although Gallaudet University was devoted primarily to the higher education of the deaf, in the 120 years between its founding and the Deaf President Now movement, all its presidents were white, hearing men. The lack of representation of the deaf in the administration was pointed out by deaf students, staff, and faculty, with many hoping that a deaf candidate would be selected in 1988. There were three qualified presidential candidates; one hearing, two deaf, and it was expected that Gallaudet would soon have a deaf president. However, the Board of Trustees selected the lone hearing candidate, Elizabeth Zinser, shocking many. Tim Rarus, one of the student leaders, described the reactions of students to the announcement, saying, “It was like we had been punched right in the face. We couldn’t believe that Zinser had been chosen as our seventh hearing president. It couldn’t be true. Our spirits sank. Obviously, they didn’t understand how we felt. But then, we started really getting angry.”

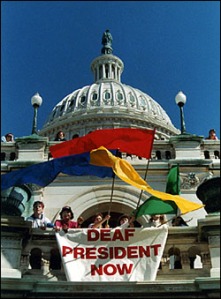

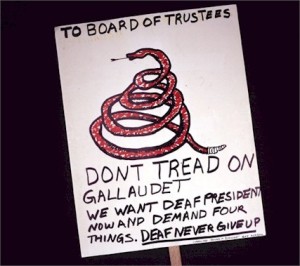

In order to protest the decision, Gallaudet students refused to go to class and shut down the campus to protest the decision, saying that they would continue to do so unless their four demands were met: 1) Elizabeth Zinser resign and a deaf president be selected, 2) the current chairman, Jane Spilman, of the Board of Trustees resign, 3) 51% majority of deaf members on the Board of Trustees, and 4) no reprisals for anyone involved in the movement. The purpose of these four demands was to increase deaf representation in the Gallaudet administration. The student protestors were aided by Gallaudet staff and faculty, many of whom disagreed with the decision. The activists also appropriated the “I Have a Dream” slogan from 1960s civil rights movements, saying, “We Still Have a Dream.” They also had their very own “March on Washington”. Mentioning this is significant because it is an illustration of how social movements can build off from past movements, but it also has negative connotations, implying that the civil rights movement is over and done with.

As the protests grew, national and media attention grew, and many mainstream news media outlets devoted a large amount of positive coverage to the Deaf President Now Protest. President I. King Jordan explained just how much media coverage was devoted to Deaf President Now, saying, “DPN was on the front page of the Washington Post seven straight days. I’m not sure how many things appear on the front page seven straight days. DPN was on the front page of the New York Times five out of seven days. DPN was the lead story on local TV every night and often on national TV. The media was not neutral. The media really supported DPN.”

Although the Deaf President Now movement initially faced a large amount of resistance from the Board of Trustees, all of their demands were met fairly quickly, especially in comparison to other activist movements, such as the civil rights movement and women’s rights movements. I. King Jordan, a deaf man, was selected and served as president for over fifteen years. The two presidents after him have also been deaf, showing the enduring legacy of Deaf President Now. There are several factors that played a role in the speedy success of the Deaf President Now movement. For one, it is important to take into consideration the demographics of the student protesters. The majority of the students were white and middle-class, which may have played a role in the largely positive media coverage of the movement, compared to other youth-led activist movements, such as the ones in Baltimore and Ferguson. The stated demands of the protesters were also clear and relatively simple to meet, as in, they did not require large-scale changes in legislation or institutional changes outside of Gallaudet University. Furthermore, the protest was confined to a relatively small and isolated segment of society. The Deaf President Now movement, although it attracted national attention, was focused mainly on Gallaudet University and actually involved only the Deaf community. Pinpointing the reasons why the Deaf President Now movement was so successful, especially compared to other activist movements, gives vital insight on what exactly can limit an activist movement.